Published February 15, 2021

Data Science, History Students Team Up to Uncover NYC Immigrant Lives

New York City was a rapidly growing place in 1900. Immigrants represented more than a third of its 3.4 million inhabitants and were transforming the city into the diverse and cosmopolitan global capital it is today. Who were these 1.3 million newly-arrived New Yorkers, and what were their day-to-day lives like? Using big data analysis and interdisciplinary collaboration, 22 NYU Shanghai students spent their summer unearthing their stories.

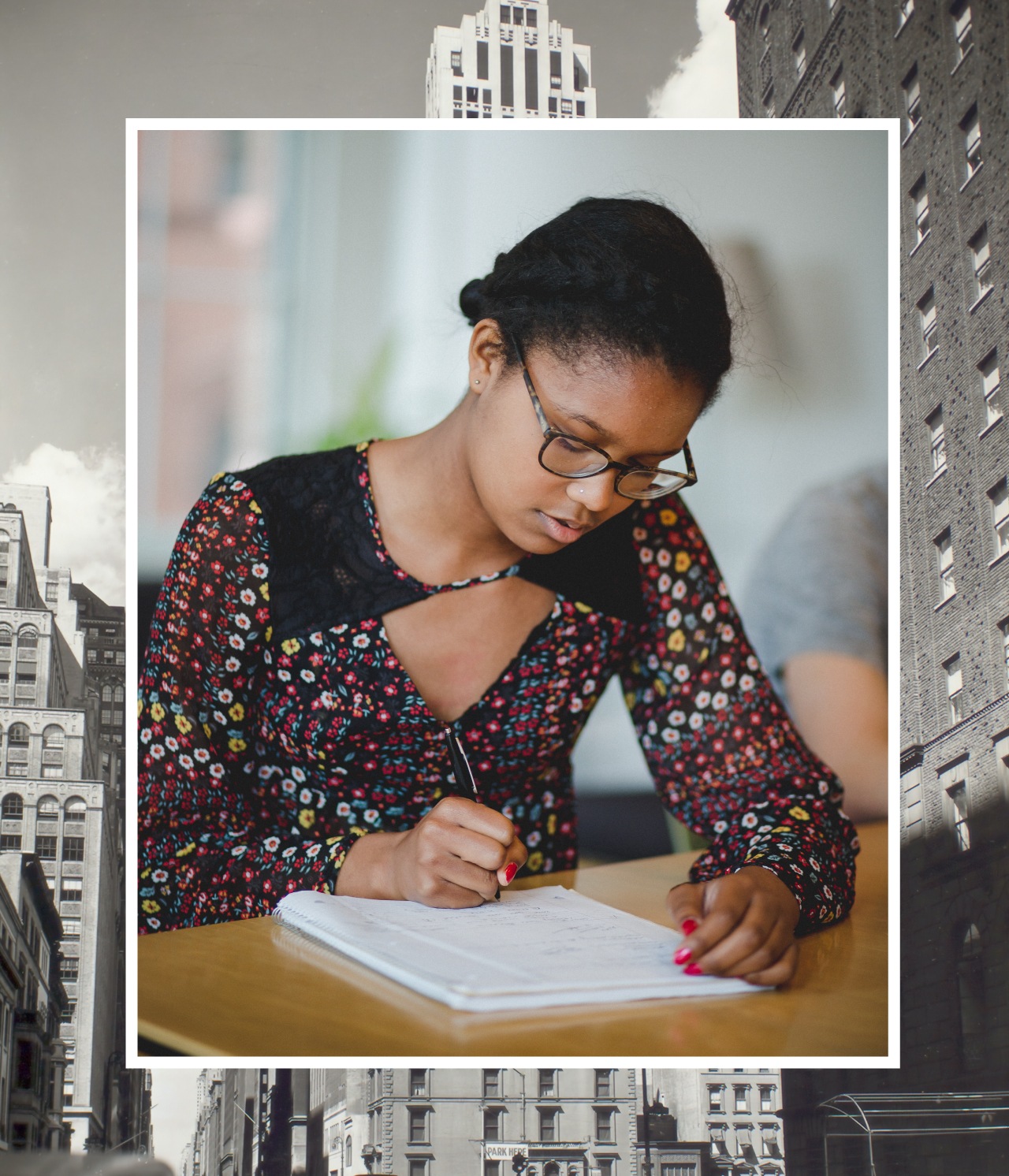

Their work is part of the Humanities Research Lab, a semester-long lab led by NYU Shanghai assistant professor of history Heather Lee. She first launched this student-driven research project in Spring 2018 with David Ludden, professor of history at NYU. Over the past four semesters, Lee has led students from all three NYU campuses in digitizing, analyzing, and tying together millions of entries from the United States’ first big data source, the US Census, and hosts of other sources—business directories, licensing records, historical maps, and other population surveys—enabling student researchers to identify significant patterns in immigrants’ life paths. The goal is to leverage digital technology to tell nuanced and compelling interpretations of the immigrant past.

“If we don’t have diaries, if we don’t have a robust amount of letters, how can we still get at the immigrant experience? Data and data analysis is one way of doing it.”

The students—whose majors spanned the humanities, business and finance, and computer and data science—worked in four interdisciplinary research groups. Each group worked on one major data-mining and data-refining task, whether that was teaching computers how to read historical documents better, finding new ways to determine restaurant owners’ nationalities, or determining immigrants’ income levels and legal work status.

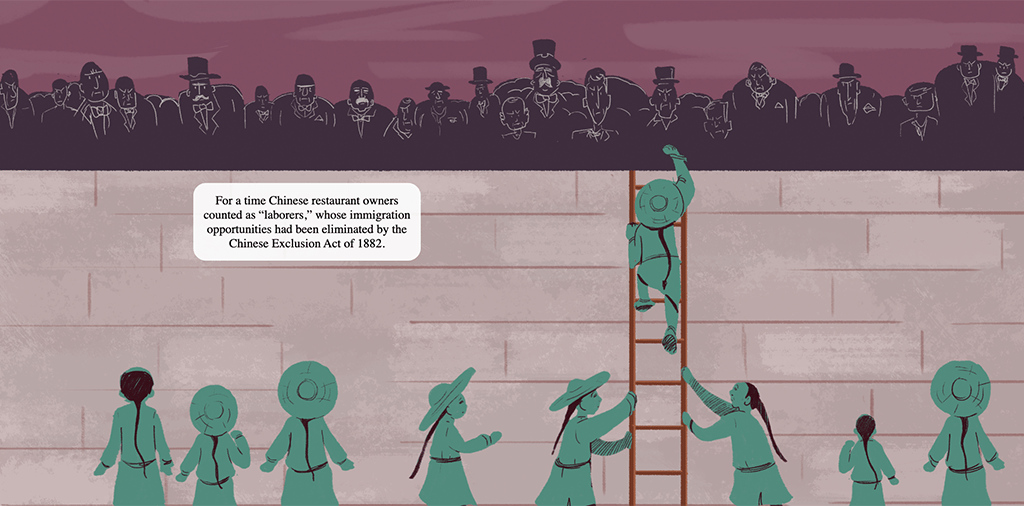

“As a historian, it can be frustrating to want to study people who are excluded from conventional archives, whose thoughts and experiences weren’t considered important by historical institutions,” said Lee, whose current research focuses on the history of Chinese restaurants in the United States. “If we don’t have diaries, if we don’t have a robust amount of letters, how can we still get at the immigrant experience? Data and data analysis is one way of doing it.”

“Learning how a different discipline might be asking, ‘What can we learn from this source?’ in a different way opens up new avenues for resolving the silences and gaps in the historical record, so we can give voice to marginalized immigrants,” Lee said.

Tim Wu Guangyu ’20, whose “US Census” team linked US Census entries for 1880, 1910, and 1940 with data from other historical sources, said Professor Lee’s ideas about using data to uncover the stories of ordinary people inspired his team to take the data into a new realm.

“Since the data collected in the historical censuses is often incomplete, we tried to leverage machine learning to predict the socio-economic status of people who don’t have complete information, using more commonly available variables like occupation and age,” Wu said.

“We hope to tell data-supported narratives of ordinary immigrant groups in order to make the historical narratives as inclusive as possible.”

Wu’s teammate Zhang Shaoyu ’21, a Humanities major, helped her data science peers use broader historical context to identify which population categories and city wards could give them the most comprehensive data. Zhang and her teammates eventually found that they could use income level calculations and ethnicity information to create a “dissimilarity index.” These calculations illustrate the relative level of segregation or integration of social and ethnic groups across all of early 20th-century Manhattan.

Computer Science major Jennie Shen Mengjie ’22, whose team expanded an existing database of Chinese restaurant owners and workers, worked primarily on creating a new field of data—Chinese immigrants’ legal immigration status in the United States. She was surprised by the amount of background knowledge she needed to complete just one column of data, often spending hours combing through historical legal case files to determine a single worker’s status.

“When I’m using computer science thinking paths, I’m usually looking at things from a more micro perspective, focusing on one data point like how many people are immigrating to New York from a certain place,” said Shen. “But when I was doing this project, especially when I was trying to search for legal cases, I actually had to take a more macro perspective to see how one single person’s life path developed.”

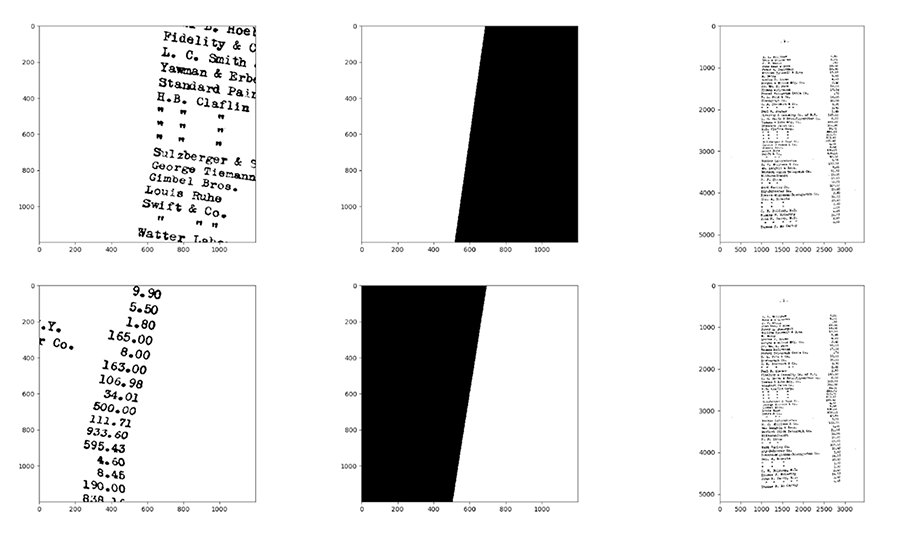

One team also worked closely with Adrian Hodge and Dai Yun from the NYU Shanghai Library’s Research and Instructional Technology Services team, developing skills in a variety of technical tasks like Optical Character Recognition (OCR) and using Geographic Information Systems (GIS) to visualize data.

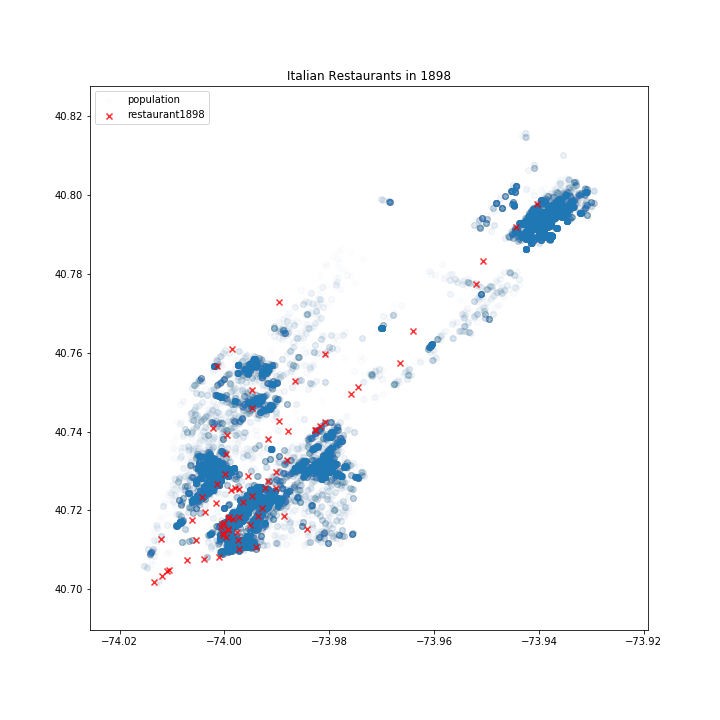

Cinny Lin ’22, a Data Science major from Taipei, worked in the project’s “Restaurant” group finding the nationalities of restauranteurs listed in New York City’s late 19th-century business directories using an Application Programming Interface (API) and US Census data, among other sources. Lin ultimately plotted restaurant and immigrant community locations on a map of Manhattan, finding that “ethnic” restaurant clusters didn’t always align geographically with places where clusters of immigrants lived, as the group had originally assumed they would. This led Lin and her teammates to wonder who those restaurants were serving, and how their data might illustrate changing ideas about consuming food from outside one’s own ethnic group.

“It was only this summer with this project that I finally saw how transformative and how empowering data analysis can be, but I also saw what it lacked and how I need to make up for this with more background understanding,” said Lin. “I’m not just applying data science skills—I have to have some way of backing up my data analysis with context to actually understand the insights that the data shows.”

Lessons like these are key to becoming a responsible and effective computer and data scientist, said Assistant Professor of Practice in Computer Science Gu Xianbin, who consulted with the Humanities Research Lab this fall.

“I was excited to see a lot of innovative application of state-of-the-art machine learning techniques in these projects, for example the use of several erosion and boundary detection algorithms to aid image processing,” Gu said. “These projects demonstrated the power of the cooperation of data science and humanities research, which, I believe, will benefit both disciplines.”

Humanities Research Lab will continue to look at the immigrant experience through big data research in Spring 2021. Students interested in joining the project can sign up via Albert and are encouraged to contact Professor Lee directly via email.

![IMAGE 1: [NYU BOBST CARD CATALOG IS A WOODEN BOX CONTAINING DRAWERS OF INDEX CARDS ]](https://meet.nyu.edu/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/cover-hero2.jpg)