What would you do if your city faced a disaster that could happen any time between tomorrow and 100 years from now—or perhaps longer? That’s the dilemma facing over 350,000 residents in Campi Flegrei, a restless volcanic region near Mount Vesuvius in Italy. This summer NYU students investigated this question for themselves. Naples: Theatre of the Earth, a study abroad course, combines volcanology and theatre techniques to explore the science behind volcanic activity and creative approaches to communicating it.

“Students from any discipline can find a way into this course. So, what matters most is curiosity and a willingness to slow down,” says Kristin Horton. She teaches the course with fellow NYU Gallatin School of Individualized Study professor Karen Holmberg. “We pose a lot of simple yet surprisingly challenging questions. For instance, we ask, ‘How do you notice where you are? What does it mean to listen to and see a place?’ We use tools like sensory mapping, ensemble exercises, and place-based research. This helps students develop a capacity to integrate the artistic with the scientific. By doing so, we can expand upon our research questions.”

Learn About Volcanic Activity Right Where It Happens

The class explores bradyseism, a term describing the slow rise and fall of the earth in areas with volcanic activity. To better understand this process, students visited sites of seismic activity. These included the volcanic craters of Solfatara and Lake Avernus, the Puteoli marketplace, and Pompeii, the city famously destroyed by Mount Vesuvius in AD 79. As they toured the areas, students studied data on past geophysical activity, gas emissions, and the risks of eruptions. Additionally, they learned about the historical and cultural significance of the areas.

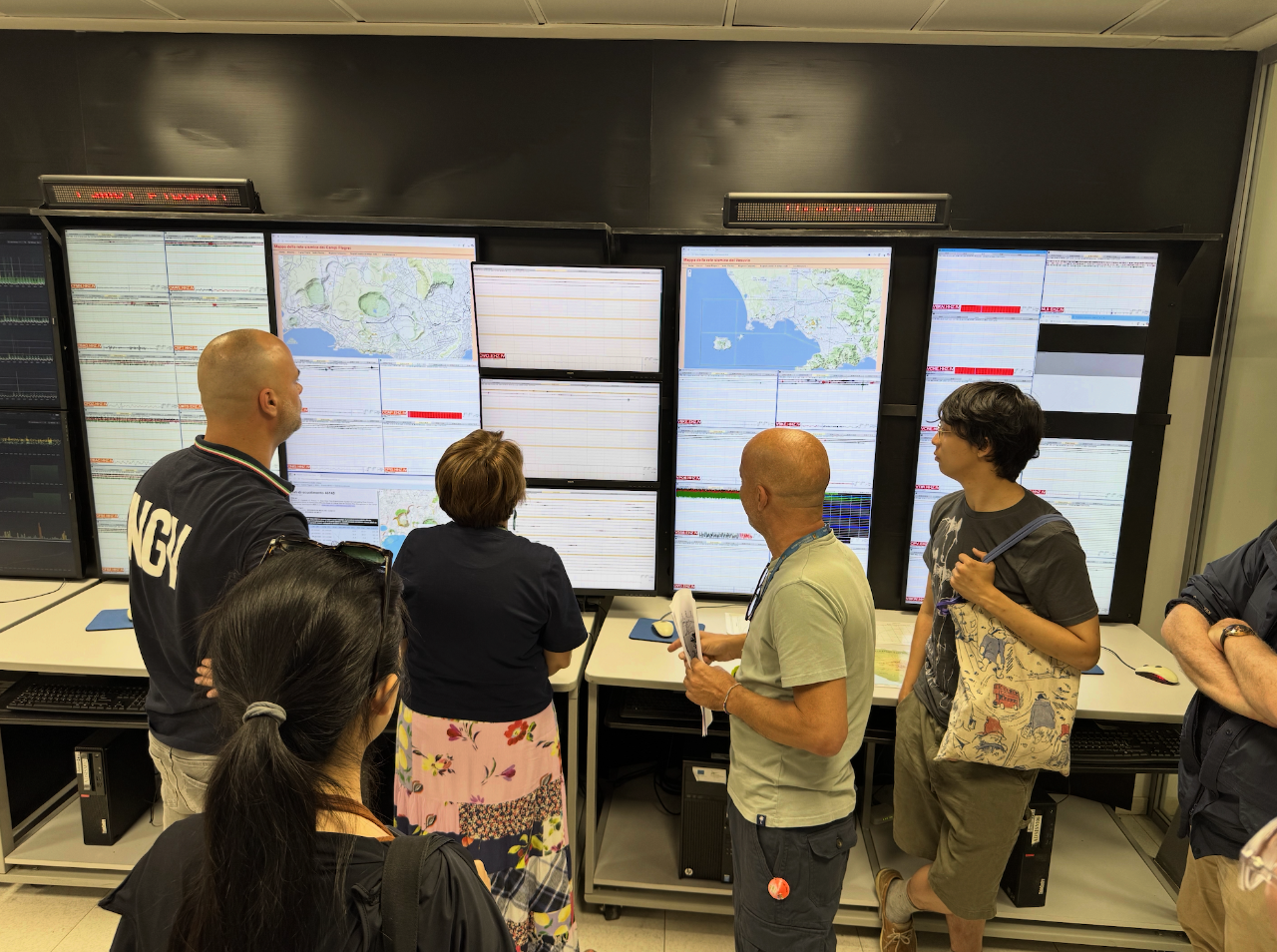

The class also took a trip to the National Institute of Geophysics and Volcanology Vesuvius Observatory. Here, students got a firsthand look at how data is collected via the observatory’s 24-hour monitoring room for volcanic and seismic activity in the region.

“Seeing volcanological practice in action offered a very different perspective of the field,” says Gallatin student Abby Betts. What’s more, she adds, it was a unique experience studying the volcano from a scientific and personal perspective. As a result, she became aware of the “dangers the volcano poses both in general and to the monitoring room itself, due to its position within the red zone of Campi Flegrei.”

Help Create a System to Raise Public Awareness

Last year a resurgence of tremors in Pozzuoli, Italy, created newfound concern among residents and government officials that a natural disaster was imminent in the densely populated city. This fear not only prompted evacuation drills but also highlighted the need for effective communication regarding future risks.

“While these earthquakes make people very nervous, there’s almost a sense of, ‘Well, the risk has gone down, right?’ Because two separate times you had these major events and then there was no volcanic eruption. There was no major ejection of any kind of material from the subsurface,” says Holmberg. “In fact, from physics-based predictive modeling, the risk is higher because you’ve had this movement occurring. And it hasn’t been able to release. You’re dealing with uncertainty. And it’s very difficult to convey scientific uncertainty in a way that’s clear and meaningful to the people who need that information.”

To learn how to raise public awareness, students collaborated with local groups who use theatre for social action. One such organization, Archè Teatro, had students participate in physical and improvisational exercises, rhythm games, and silent listening walks. They also practiced breath and gesture sequences to deepen their engagement. “These methods helped them tune into their bodies as instruments of learning,” explains Horton. “They trained students to notice each other, the spaces between people, the texture of a room, etc.”

A Fresh Look at Where Art Meets Science

Ultimately, the theatre sessions gave students a deeper appreciation of the ways in which art and science intertwine. Going forward, they can use these skills to connect with communities and convey scientific data.

For Holmberg, the uncertainty surrounding what could happen in Campi Flegrei—and when—offers lessons for how we might approach climate change across the globe. “When a problem is too big, it becomes difficult to see and respond to on an individual level,” she says. “Campi Flegrei is a very special and specific example of grappling with environmental risk. But it is also a proxy or litmus test for the challenges we face in many parts of the planet.”

We appreciate the team at NYU News for sharing this story with us! This story was reported on and written by Jade McClain, and you can read it in its original format on their website.